- Home

- Liza Kleinman

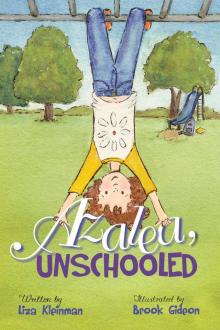

Azalea, Unschooled

Azalea, Unschooled Read online

Other Middle Reader and Young Adult books by Islandport Press

Cooper and Packrat: Mystery on Pine Lake

Cooper and Packrat: Mystery of the Eagle’s Nest

by Tamra Wight

Lies in the Dust:

A Tale of Remorse from the Salem Witch Trials

by Jakob Crane and Timothy Decker

Billy Boy:

The Sunday Soldier of the 17th Maine

by Jean Mary Flahive

Uncertain Glory

by Lea Wait

The Fog of Forgetting

by G. A. Morgan

Mercy: The Last New England Vampire

by Sarah L. Thomson

ISLANDPORT PRESS

PO Box 10

Yarmouth, Maine 04096

www.islandportpress.com

[email protected]

Copyright © 2015 by Liza Keierleber

Illustrations copyright © 2015 by Brook Gideon

First Islandport Press edition published May 2015

All Rights Reserved

ISBN: 978-1-939017-59-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014911180

Book jacket design: Karen Hoots/Hoots Design

Book design: Michelle Lunt/Islandport Press

To Anya

Contents

Chapter 1: Unschool Meeting

Chapter 2: Unschool Bus

Chapter 3: Unschool Colors

Chapter 4: Unschool Playground

Chapter 5: Unschool Lunch

Chapter 6: Unschool Library

Chapter 7: Unschool Trip

Chapter 8: Unschool Board

Chapter 9: Unschool Break

Chapter 10: Unschool Reunion

Chapter 11: Unschool Work

Chapter 12: Unschool Cheer

Chapter 1

Unschool Meeting

The first time I met Gabby, she was in a big mollusk phase and had baked some experimental snail cookies.

“Try one,” she urged, holding out a plate.

I didn’t even know her name yet. I had just moved to Maine, and was standing in a stranger’s living room at a party for homeschoolers. Every place we’d lived—and there had been a lot of them—my mother had always made sure we met other homeschoolers. She said it was important to be part of a community.

Gabby, still offering me the plate, took a cookie for herself and had a large bite.

“They’re delicious,” she said encouragingly.

The cookies were lumpy and swollen, and each one had two thin pieces of black licorice sticking out. I weighed my love of cookies against my lukewarm feelings toward snails.

“Are those supposed to be antennas?” I asked, stalling for time.

“Tentacles,” she explained, chewing. “Mollusks have tentacles.”

Then she laughed, covering her mouth just after the crumbs sprayed onto me. She had golden-brown hair, thick and curly, that was the exact same color as her skin and her eyes. Everything about her was golden-brown.

“You didn’t think the cookies had actual snails in them, did you?” she asked.

I gave her a nervous smile.

“No,” I lied.

“They’re just shaped like snails,” Gabby said kindly, brushing the crumbs from my shoulder. “I should have explained that.”

She examined the remains of the cookie in her hand.

“I guess they’re not even so snail-shaped, after all. They looked swirlier before I baked them.”

I took a cookie and had a bite. Chewing gave me an excuse to look around for a while before I had to talk again.

The room was enormous—it was the biggest living room I’d ever seen. Giant paper words hung from the ceiling: EXPLORE. CREATE. QUESTION. WONDER. DO. I’d never been to a party that provided so many directions. Was I supposed to do all of these things at once, while eating snail cookies, or could I tackle the list one at a time?

There were a lot of adults in the room, wandering around and talking to each other, but only a few kids. My mother was having a conversation with another parent, and my sister Zenith sat slumped in a chair near the food table. She looked annoyed. She was thirteen, two years older than me, and she almost always looked annoyed.

I swallowed my piece of cookie and was about to ask Gabby if she knew most of the people here when a woman climbed up onto a chair. She had greeted us when we’d arrived at the party. It must be her house, I figured, especially since she was allowed to stand on the chairs. She began tapping a spoon against a glass for attention, even though everyone was already looking at her.

“Hello, hello!” the woman shouted, still tapping. Her gray-blonde hair tumbled wildly, and with her spoon-holding hand she gave a little wave that almost threw her off balance. The buzz of conversation died down.

“I’m so glad to see all of you here today,” the woman said. “For those of you who are seasoned unschoolers, thank you so much for coming to share your experience. And I want to give a warm welcome to those of you who are homeschoolers, or even, dare I say”—the woman lowered her voice and delivered the end of her sentence with a dramatic quaver—“schoolers.” There was laughter.

“That’s my mom,” whispered Gabby.

So she lived here, in this beautiful old house filled with furniture that looked like someone had carved it. My family had just moved into an apartment. It was nice enough, but I had been hoping for a yard. This house, I had noticed when we arrived, had lots of land around it.

“That’s nice that your mom organizes meetings for homeschoolers,” I said, whispering now, since all attention was on the host. “We just moved here. My mom is always looking for other homeschoolers for us to get together with. I guess that’s how she found out about this party.”

Gabby looked at me in surprise.

“Unschoolers,” she said, a little too loudly. “This meeting is about unschooling.”

Before I could ask what the difference was, Gabby’s mother continued speaking. She still held the spoon and the glass, but she had stopped tapping them together.

“Let me introduce myself,” she said. “For those of you who don’t know me, I’m Spirit, and I want to thank you all for coming here today with open minds and adventurous hearts.”

“Spirit?” I whispered, not very politely.

“She’s calling herself that now,” Gabby whispered back. “Her real name is Muriel.”

Spirit continued.

“For us, unschooling has been a wonderful journey, and we’re so excited to have your company. I know that some of you here are homeschooling, and I’d like to congratulate you on taking the first step away from an outdated, stifling idea of childhood.” Spirit paused, beaming.

There was a stir of activity in the room as the parents looked around at each other, trying to figure out whether to be proud or insulted. I wondered if Mom would be annoyed that this had turned out not to be a homeschoolers’ meeting at all. She probably wouldn’t care too much. She would just as soon be at a meeting, any meeting, than home unpacking with Dad. She liked meetings; she didn’t care for unpacking. Still, I had been hoping to come back to this house, to play in the large yard with this new girl. I hoped that wasn’t ruined now.

“I’m Gabby,” she said softly, holding out her hand.

I took her hand and shook it. I had never actually shaken someone’s hand before. It seemed like something adults did, maybe at important business meetings.

“I’m Azalea,” I replied.

“Pretty name!” said Gabby.

“Thanks. It’s a kind of flower. My sister’s name is Zenith. It means highest point.”

“That’s an interesting name.”

“The funny thing,” I told her, “is that it used to be a brand

of TV. A long time ago. Sometimes when Zenith is being particularly boring, I’ll hold my hand toward her like a remote and pretend to change channels.”

Gabby giggled. “That’s funny.” She paused. “I wish I had an interesting name. But I came with the name Gabby, so my mother kept it.”

I wasn’t sure what that meant. I hoped Gabby would explain, but she didn’t.

Spirit continued speaking.

“I’d like to encourage you all to join us in taking the next step. As homeschoolers, you understand the value of letting your children learn at a pace and in a manner that suits them. Why, then, should you cling to the last shred of the old model—the one in which the deciding figure is the teacher, or, in this case, the parent? Why not give each child the freedom to discover his or her own truth?”

Gabby looked like she’d heard all of this before.

She also seemed unsurprised when a tall, skinny girl dressed entirely in pink ran up and grabbed her.

“Gabs!” the girl shrieked. She didn’t appear to care that Gabby’s mother was still talking. She surrounded Gabby in a hug, smothering her with her pink-sweatered arms. Even her jeans were pink.

“Hi,” said Gabby, hugging back, still keeping her voice low. She pointed at me. “This is my new friend, Azalea.”

I felt pleased. Already I was Gabby’s friend! I was pretty sure Zenith hadn’t made a friend yet. She was still slumped in her chair, gazing across the room at a chubby blond teenage boy who wasn’t gazing back.

“Azalea, this is my friend Nola. She unschools, too. We do a lot of stuff together, projects and things.”

Nola gave me a hard look. “Are you going to unschool?” she asked.

“I homeschool,” I explained. “I think my mother thought this was a homeschoolers’ meeting.”

“Too bad,” said Nola coolly, then turned back to Gabby.

“Gabs, come with me. I have stuff to tell you.”

“Nola,” Gabby said, “Azalea just moved here. She’s new in town.”

“I heard,” Nola replied. She looked at me again. She studied my face, and I got the uneasy feeling that she knew something about me.

“Come on.” Nola grabbed Gabby by the arm and yanked her off into another room.

Gabby turned toward me as they left, and called softly, “Talk to you later!”

I lifted a hand in a wave.

Spirit wound up her speech and commanded everyone to mingle. Now that Gabby was gone, I didn’t know who to talk to. I moved toward Zenith’s chair and stood next to it. Zenith did not acknowledge me. She chewed absently on a chunk of bread dipped in green-flecked hummus.

“I met the girl whose mom was speaking,” I told her.

Zenith nodded. She was still looking across the room at the boy, whose head bobbed rhythmically between a pair of earbuds.

“Do you know who that is?” she asked, jutting her chin toward him.

“No,” I said. “I don’t know who anyone is except that lady and her daughter and the daughter’s annoying friend.”

“That’s three more than me,” Zenith pointed out. She ran a hand through her long, straight dark hair. I had always envied Zenith’s hair. It was far more interesting and dramatic than mine, which was light brown and sort of cloud-shaped.

I spotted Gabby across the room, near where Spirit had been talking. Nola seemed to have disappeared, which was good. I went to talk to Gabby again, and Spirit rushed up, her long skirt rustling, her jungle of hair floating behind her. She ignored me.

“Gabby,” she said, “where’s your brother? We need chairs.”

Gabby pointed to the boy wearing the earbuds.

“Gibran!” shouted Spirit. Everyone at the party turned except for Gibran. “Go get chairs from the garage!”

Gibran remained seated.

“And off he hustles,” said Gabby, “breaking all records for speed!”

Suddenly Zenith appeared next to him. “I’ll help you,” she offered.

Gibran looked irritated, but he eased himself from between the earbuds and walked to the door. Zenith followed. I could hear her chattering at his back as they left. When they came back they were lugging folding chairs.

“Right here,” directed Spirit, who was at once chatting with guests, ladling mugs of squash soup, and arranging furniture. No one sat in the chairs, but Spirit seemed satisfied, and whirled off to another part of the room.

I pointed to one of the signs hanging overhead.

“Did you make these?” I asked.

“No,” Gabby replied. “That’s a Spirit thing. I’m just the cookie maker.”

This reminded me that I’d left the rest of my snail cookie on the plate, which was now across the room from us. I didn’t feel like winding through the sea of people to find it.

“So, you live here?” I asked Gabby. I tried to imagine having a house like this. I could live on a whole different floor from Zenith, instead of sharing a room with her.

“Yes,” she said. “All my life, just about. How about you—have you ever been to Maine before?”

“No, not until we moved to Portland last week,” I said. “My dad is going to drive a tour bus.”

Now that I’d said it aloud, it sounded strange. Who drove a tour bus in a city that was completely new to him? Dad did. It only sounded strange if you didn’t know him.

Gabby didn’t appear to notice. “So where did you live before?”

“Oh, different places . . .”

I wasn’t sure how it would sound to her, the way we had moved around. I could barely remember all of the places we’d lived. The earliest I could remember was Philadelphia, where my parents had run a sort of clothing boutique for pets. Dog hats, cat pants—if it would embarrass a pet, they carried it. That hadn’t lasted long. Then they’d owned a sewing supplies store in Florida, called Darn It All, followed by an all-you-can-eat breakfast buffet in North Carolina. I could still remember the sickening smell of scrambled eggs in big metal bins. Most recently, they had taken a stab at running an apple orchard in Connecticut. It might have worked out, my father thought, if not for a late frost.

“Well, I’m glad you’re here now,” said Gabby.

“Me, too,” I said, and I meant it.

We watched Gabby’s brother and Zenith, who was still talking, even though Gabby’s brother was listening to his music again. She hadn’t said that much to me in the past year.

“So that’s your brother?” I asked Gabby.

“Yeah,” Gabby said. “He’s fifteen.”

“Does he unschool, too?” I asked.

“He does,” said Gabby. “But I don’t think he’s that good at it. He mostly just sits around. He is building a boat, though.”

“He doesn’t look like you,” I said.

Gabby didn’t look quite like anyone I had ever seen.

“Gibran is Spirit’s biological son,” Gabby explained. “I’m adopted.”

“Oh,” I said.

I’d known plenty of other families with adopted kids; why hadn’t I figured it out?

“How about you and Zenith?” Gabby asked.

“We’re both”—I remembered Gabby’s word—“biological. Although sometimes I think Zenith came from another planet.”

We laughed.

“Sometimes I think I did,” said Gabby, but she wasn’t laughing anymore. She looked a little dreamy.

“Planet of the Snails?” I asked.

This made Gabby laugh again.

“Yes,” she said. “My birth mother was a squid. They’re mollusks, too, you know, like snails are. Huge ones.”

“Wow,” I responded. “I didn’t know you were a secret squid!”

“Maybe you are, too,” Gabby said. “Maybe we’re Secret Squid Sisters!”

Nola appeared behind Gabby just as she said this. I had hoped she’d left.

“Me, too!” Nola shouted. A couple of people turned to look. Nola didn’t care. She seemed more like Spirit’s daughter than Gabby did.

“I

want to be a Squid Sister, too!” Nola said, grabbing Gabby’s hands and dancing in a circle with her, like that was some kind of a squid thing. For all I knew, maybe it was. Maybe unschoolers were the world’s leading experts on squid. Personally, I was more interested in history, but to each her own.

Gabby pulled one hand from Nola’s and held it out to me, but Nola yanked the hand back and turned away to make it clear the dance did not include me.

Message received, I thought.

Chapter 2

Unschool Bus

“So,” Mom asked Zenith and me on the way home, “what did you think of the party?”

“Boring,” said Zenith, not unpredictably. She was riding in the passenger seat next to Mom.

“Fun,” I corrected from the backseat. “Good food. And I really liked that girl, Gabby, the one whose mom did the talking.”

“I saw you talking to Nola, too,” Mom said. “The girl dressed all in pink. Do you know who she is?”

Sure, I thought. Gabby’s obnoxious friend who hates me.

“That’s Jack’s niece. You know, Jack—the old friend of Dad’s who sold him the tour bus. The guy who moved to Florida. That’s how I heard about the meeting today. He knows that we homeschool, and he got me in touch with some people.”

So Nola’s family was responsible for our owning the bus and for our being at the meeting. I remembered the way she’d looked at me when Gabby introduced us. She had known something about me, after all. Gabby probably knew, too. I was the only one who had been kept in the dark. Zenith, too, but she probably wouldn’t care.

“The meeting,” Zenith broke in, “was about unschooling, whatever that is. Why did we even go? I thought it was going to be a homeschooling thing.”

“I think the idea of unschooling is kind of interesting,” Mom said carefully. She held up a finger—Give me a minute—while she studied a street sign and then squinted at a sheet of paper with printed directions. “I think it’s this way,” she said, turning the car. “Anyway, it’s a whole different philosophy. Unschooling. It’s really about not imposing a structure on the natural curiosity of a child. I’ve been doing some reading about it.”

“I see,” said Zenith. “The last time you were doing some reading about something we ended up eating oatmeal and kale at every meal for a month.”

Azalea, Unschooled

Azalea, Unschooled